New Belgium puts its

sour beer program on tour each year with its Sour Symposiums, offering a rare

and direct insight into the history and mechanics of its sour beer program

presented by Eric and Lauren Salazar. The focus of the event is La Folie and

provides the opportunity to taste beer drawn from some of the individual

foeders and get a taste (pun intended) of what makes the La Folie blend. Given

the rarity of the event and the information gleaned I thought it was worth

sharing my notes here. I'll touch on a few pieces of the history Eric and

Lauren shared and then move on to discussing the La Folie blend, how Lauren

thinks through the blend and then my tasting notes on the individual foeders.

The History

In the beginning, in

1998, it was just seven barrels (not foeders, just regular ass barrels) which

has grown into a massive space of foeders (and some barrels) especially with

the expansion over the past few years. The barrels had been inoculated with

various microorganisms but the character of their sour beers really developed

after an account returned a keg of Fat Tire that had soured and they used some

of this sour Fat Tire to further inoculate the beers. (This story is believable

but I do wonder, just a little, whether this is some fanciful storytelling to

create a nice link between New Belgium's core beers and the sour beers.)

The first bottling from

the sour program was La Folie in 1999. The staff felt confident they would

knock out the bottling and party afterwards. A hot tub was rented. Nobody got

in the hot tub. Instead of an easy bottling session the staff was subjected to

a complete nightmare. Everything seemed to go wrong. The bottling run was small

to begin with but was further depleted due to problems packaging the beer. That

first year La Folie went into a corked and caged 750ml champagne style bottle.

The problem was that the corks they purchased were too big (likely designed for

the mushroom-style Belgian bottles) and the corks were cracking the bottles.

Yikes.

That kind of mistake

seems so obvious in 2016 but looking back seventeen years ago there were very

few people available to teach how to do these things and perhaps more

importantly what not to do. They were learning by trial and error and most of

what has become the pool of knowledge between Eric and Lauren was built by

trial and error through the years. There were some times where people were able

to teach important lessons. For example, when Lauren first experienced a

pellicle her first impression was that this was not a good thing and spent some

time stabbing the pellicles. Vinnie Cilurzo quickly set her straight when she

brought up the mysterious film on her beers. So let's talk about some of the

things they learned that helped develop their sour program.

The New Belgium Sour

Program

I don't want to repeat

too much of the basic info that's available about their sour program but just

enough to provide a jumping off point to discuss some of the info I obtained

that isn't floating around the intertubes and other media. New Belgium brews

two beers for its sour program, Felix and Oscar. Felix is a pale lager while

Oscar is a dark lager closely modeled on 1554. The beers are fermented with

lager strains, centrifuged and then top up the foeders as necessary. The

blended beers produced from these two base beers are blended out of the foeders,

pasteurized and bottled.

New Belgium's sour beer

program is unique in many ways, at least among American sour brewers. Their

core use of foeders creates a different aging environment from most and their

choice of base beers is also atypical. The overall process and choices they

have made is a function of lessons learned over almost twenty years plus

undoubtedly Bouckaert's experience at Rodenbach. Their attitude about secondary

fermentation is also unique. While most sour brewers think about brett as driving

flavor in sour beer, the Salazars look at brett primarily as a mechanism to

prevent acetic acid. One has to imagine at least part of this attitude comes

from using foeders that were often discards from the wine industry of various

quality and the large surface of the beer in those vessels. But before

discussing the foeders a little more let's go back and talk about those base

beers.

The use of lagers as a

base for sour beer certainly cuts against the common attitude that one wants a

POF+ saccharomyces strain as a primary strain (POF+ = phenolic off flavor

positive) because brett will take those phenols and make lots of fun spicy,

earthy, barnyardy flavors out of them. The foeders create some of those flavors

(and in some more than others) but much of New Belgium's sour beer character is

something different from the expected barnyard blast (a good beer name). They

get a lot of other flavors and more subdued phenolic compounds that allow them

to stand out among a growing sea of sour beers. So then we turn to the foeders

and how they affect the base beer. It was clear from tasting individual foeders

and seeing Lauren's notes how different each foeder is although each receives

the same base beer.

The foeders all have

their own backstories and some came from some rough histories where most people

would probably steer clear of a barrel with that kind of rap sheet. Eric and

Lauren are patient and know how to make foeders loving environments. That

loving environment clearly plays a role in the development of the beer inside

and that's not just the foeder itself but where it resides in the brewery and

how temperature and humidity in that exact location may play a role. It's not

clear exactly how different the microorganisms within each foeder differs but

the difference is likely not substantial given their use of good foeders to

innoculate new foeders that enter the brewery. I also assume that part of what

was a very obvious concern for acetic acid production has to do with the use of

questionably treated foeders which may have adopted an unhealthy community of

acetobacter in which brett is critical to keeping those jerks at bay.

While we're talking

about the foeders it's worth sliding in this small but seemingly useful tidbit

I picked up. Lauren came over to my wife and I late in the session and we

chatted a little. Her voice was going out at the end and lots of people wanted

to talk to her so I tried not to woo her to stay and talk to me about the many

questions I had and just picked the one I thought was most useful. Eric had

pointed out that during the 2013 expansion of the foeder inventory that they

had figured out by trial and error that twenty percent was the magic volume of

beer from good foeders to innoculate the incoming foeders. I asked her what

misses they had experienced at other volumes. Her answer was that anything less

than twenty percent led to too slow of a secondary fermentation and they ended

up with oxidation (presumably that acetic acid) and any larger volume had no

greater effect so it was just wasting good beer that could go out to customers.

Here's why I felt that

small piece of information was so important:

1. Obviously for anybody

trying to inoculate a new fermentation vessel has one of the best data points

here in how much beer is best to make that vessel a good home. Even a normal WL

or WY pitch may not be an ideal volume to protect the beer from negative

effects of oxygen exposure, particularly if the beer is going into a barrel

where the native population may be oxygen-loving.

2. For anybody running a

solera it's a good basis for how much beer to leave behind in the solera when

pulling beer. American Sour Beer points out that New Belgium

sometimes draws to a far lower point in the foeders but if you're working on a

solera that is a non-porous vessel (i.e. not wood) and you are not leaving

behind trub with the next fill then it's probably a good volume to avoid

oxidation issues.

3. It draws into

question the typical homebrewing (and sometimes commercial brewing) concept of

unloading a small amount of dregs into a beer to trigger that wonderful

secondary fermentation. Certainly at a small level our oxygen exposure risks

are less and in a less porous vessel the risk is further diminished but I count

myself among the number of brewers who have seen a batch get oxidized and develop

either oxidized flavor or acetic compounds from lazy pellicle formation. We

should probably think carefully amount either creating starters or pitching a

larger volume of dregs than a bottle or two into five gallons. (I know many are

not so casual about sending in the troops but there are sources online

perpetuating this casualness.)

Something to think about

at least. I wish I had the opportunity to ask more about what went wrong for

them than all the things that went right because that's where the most

important lessons reside, at least in my opinion. Part of the reason why I blog

is to catalog what went wrong for me so I can help others not make those same

mistakes. But I wanted to be respectful of her time and health. I should point

out that American Sour Beer speaks on this subject at points

out in the New Belgium section that ten percent was the amount used. This seems

to be a trial and error correction on New Belgium's part. I don't think the

book is wrong for the time the information was given to Michael Tonsmeire but I

promise this information came directly out of the mouths of Lauren and Eric. I

think this is just a testament to how much they focus on learning from their

trials and errors.

Let's then move along to

talk about blending a little. I wish Lauren had talked a little more about her

paradigm on blending. She gave the same flower analogy I believe she gave on

one of the Sour Hour episodes that she starts with the middle of the

flower--what the beer should be--and adds the beers from the different foeders

like adding petals to the flower. She disclaims the analogy as girly but it

makes sense. Blending beer, in my opinion, is just like building a recipe. You

should start with what you want that beer to be and work backwards. I think her

voice was starting to go at this point so she turned to encouraging us to taste

and blend the foeder samples given to us. I don't have any mystic gems from her

about blending so I'll just offer this picture of her notes on the final blend

for 2015 La Folie. Note the smile and indifferent faces that describe her

feelings on the beers.

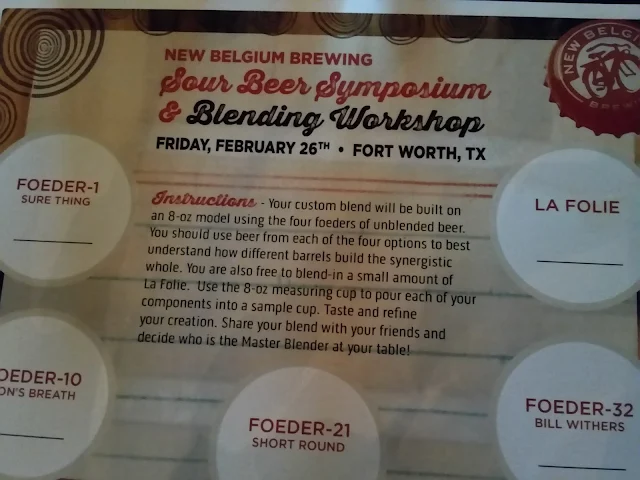

Tasting the Foeders

This was awesome and

honestly the main reason why I wanted to come to this event. The opportunity to

break down a blended sour beer into its components and really understand the

experience and mindset in blending the beer is truly incredible, especially

when it comes to walking the path of somebody as knowledgeable and experienced

as Lauren. We were only given four of the twenty-six foeders that go into the blend

but they were clearly key components of the blend and could be identified as

pieces of La Folie's character. Overall it was most surprising how much each

foeder differed from one another. There was clearly some common ground in the

base beer but the differences were apparent. Three of the four beers did feel

incomplete like they needed the blend to become a complete beer. One was great

on its own and I would happily buy that as a standalone beer. Unfortunately I

don't think New Belgium makes any single releases aside from the Leopold barrel

series.

These are my notes from

the four foeder samples. I apologize that the notes are not as lengthy as I

would have liked. I was trying to take notes on the beers while taking notes on

the presentation and then after the presentation it got very loud and Lauren

came over so I wanted to stop and talk to her.

Sure Thing #01 - Firm but soft sourness, recognizable part of La

Folie acid character, slight vinegar note. Mild dark fruit flavor and aroma.

Good base component for a blend.

Bill Weathers #32

- Moderate acidity and

aroma; interesting and prominent blackberry flavor, cola and cocoa. Complex

enough that it could (and should) be released on its own as a standalone beer.

Lion's Breath #10

- Mild acidity, typical brett

funk character prominent, herbal/floral note. Recognizable within La Folie

flavor profile. Complex and brett forward.

Short Round #21 - Most aggressive acidity of the four; tangy

lactic acidity. Some brett funk aroma; large cola flavor. Balanced with Sure

Thing creates good balance of complex acidity without sacrificing a firm acid

profile.

My blend was:

- 30% Sure Thing

- 30% Bill Weathers

- 20% Lion's Breath

- 20% Short Round

Comparing my blend

against La Folie it was clearly less complex although in fairness I had far

fewer options. My blend was considerably less acidic but more brett forward

with the blackberry note from Bill Weathers far more prominent in the blend. I

liked my blend a little more than La Folie if only because I really enjoyed

that blackberry character and wanted to restrain the acidity to let it shine

through.

Concluding Notes

Good news, Clutch is

making a return later this year and Lauren promises the sour portion will be

larger for a greater sour profile. I'm really excited. Clutch is one of my

favorite beers.

I cannot overemphasize

how much the oak plays a role in the flavor profile of New Belgium's sour

beers. They have a real sense of being lived in like the microbes have balanced

out in the environment and developed their own distinct community. Gone is the

aggressive and dominant sourness often found in younger sour beer programs

(both pro and at home). Instead they have a softer acidity and more rounded

brett character than I've only myself really found in my sour beers reaching

three years of age or my lambic solera right around year four.

That's crazy... 20% is what I use to inoculate my new sours! I pull 2 gallons out of my 6 gallon fermenter, and use that to inoculate new batches every 6 months. Works great. Thanks for the info, linked it here: http://www.milkthefunk.com/wiki/Flanders_Red_Ale#External_Resources

ReplyDeleteSeems you have a knack for sours (:>

ReplyDelete